In nineteenth-century Brooklyn, films were not modern cinematic productions, but rather individual, short-lived experiences using devices such as the kinetoscope. This device showed photographs sequentially to a single viewer using a rotating mechanism and a light source to create the effect of moving objects.

Although a public presentation of the kinetoscope prototype took place in Brooklyn, and kinetoscopes were used at the first commercial exhibition in New York as early as 1894. The actual creation of early motion pictures was due to the experimental work of inventors. Among them was Thomas Edison, whose company developed and manufactured these devices in the United States. Read more at brooklyn-trend.com.

The first movie trip for a month

So, as it turns out, one of the most prominent filmmakers of the early nineteenth century was Thomas Edison. Cinema then balanced on the edge between scientific discovery, an absolutely technical process, and artistic expression. In other words, first you figured out how to show it, and then you started to figure out what to show, so that it would be creative.

Nowadays, it seems that the way images are captured and presented to the world has changed radically, but it only seems that the basic principle remains the same. This is especially evident when you take a closer look at some of the earliest works of cinema and the technologies used to make them.

The best movie to demonstrate what and how is the film “A Trip to the Moon” by Georges Méliès, which was made in 1902. In the movie, the director virtually organized his own space mission. In general, it was one of the first films in the history of cinema to have a storyline, a set of special effects, and even the image of aliens. Some kind of friendly inhabitants of the Moon, called “selenites” in the film’s plot.

In the movie, a group of researchers crash their space capsule into the eye of the legendary “Man on the Moon.” This particular scene was iconic, a true embodiment of early cinema. “Man on the Moon became public domain in its country of origin.

The kinescope in the early days

But let’s get back to the filming technique. As you know, a moving image is a series of consecutive images broadcast at a certain speed to create the illusion of movement or action. Interestingly, this principle works equally well both in the primitive predecessors of cinema, such as shadow graphics, and in modern cinema, which is shown at a certain number of frames per second.

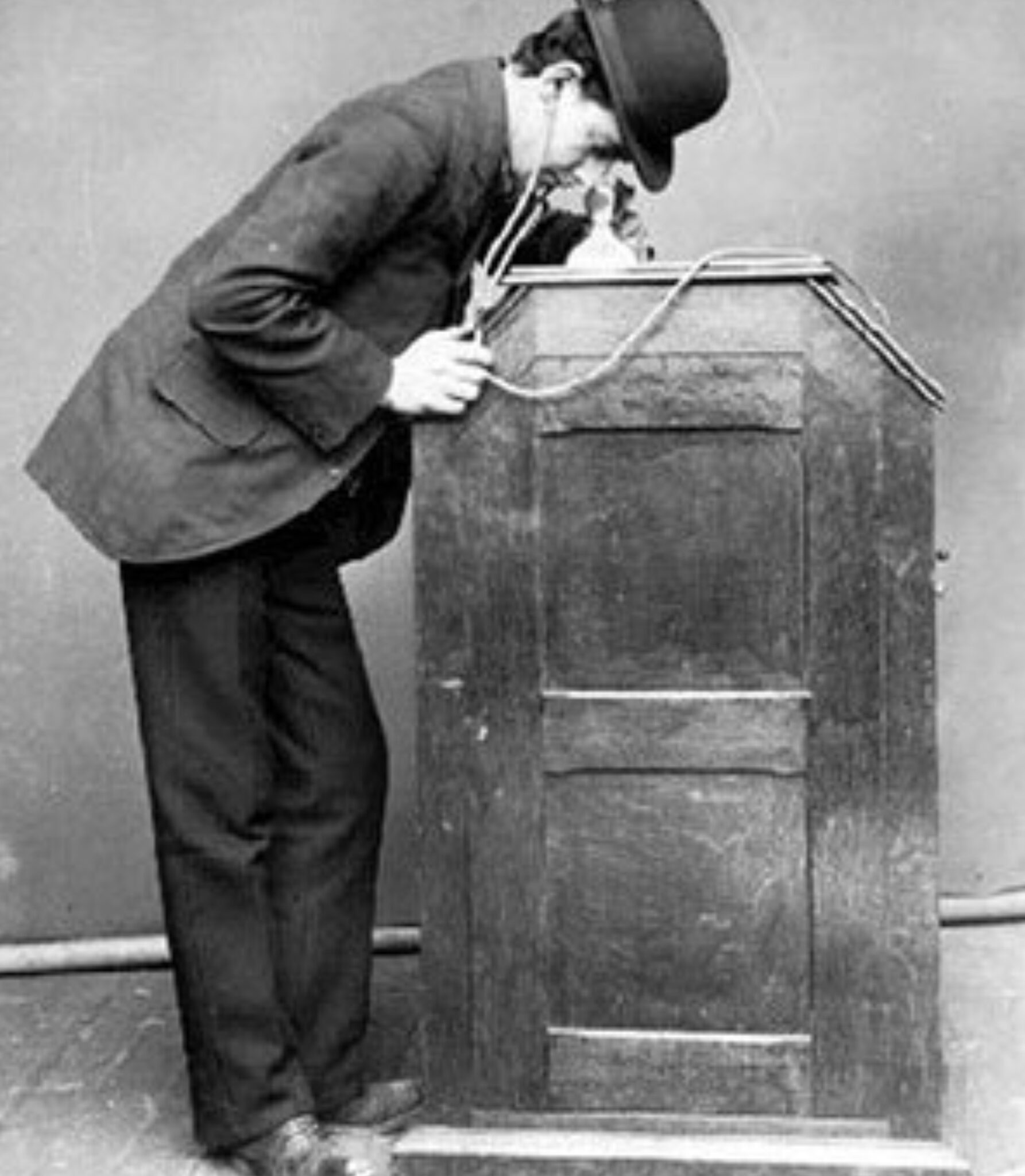

In order to make viewing convenient, it was necessary to create a unit that would reproduce the image. That’s how the kinetoscope appeared – a simple device for viewing images that was developed in the mid-1800s. The device fed a tape of film with successive photographs onto a conveyor belt. The film passed through a light source along with a shutter that moved at extremely high speeds, creating the illusion of moving images. The moving images could be observed through a peephole in the upper part of the device.

The author of this unit was Thomas Edison, who wrote about his experiments with a moving image device back in 1888. A few years later, closer to the beginning of the 20th century, he and Louis le Prance developed an improved version of the kinetoscope. Although the first versions could not be used for mass screenings, they were mostly only able to entertain one person at a time.

But when a projector was added to the kinetoscope design, several people could watch the image at the same time. The epic of invention was put to an end by Auguste and Louis Lumière, who developed and popularized a version of the device that was capable of shooting, projecting, and developing film – everything was in one invention. And the name of this invention is cinema.

Brooklyn the cinematic

When it comes to Brooklyn, the name of The Vitagraph Company of America immediately comes to mind when it comes to cinema. It was this company that stood at the origins of not only Brooklyn cinema, but American cinema in general. As for the company’s foundation, the story is quite interesting. In 1896, the English journalist and cartoonist J. Stuart Blackton, one of the authors of The New York World, interviewed Thomas A. Edison, the inventor of the kinetoscope.

In turn, Edison liked Stuart’s drawings so much that he made a movie based on them, which he called “Blackton’s Evening.” Later, the journalist shared what he had seen with his partners, Albert E. Smith, a traveling showman and magician, and distributor William Rock, who were intrigued by the emergence of something new and unknown, which would later be called cinema. So the men bought equipment from Edison. They started a new business that very few people knew about at the time, and the friends started making films.

Interestingly, their first studio was located on the roof of a building at 140 Nassau Street, right next to City Hall in Manhattan. In 1897, the friends made their first film, which was intriguingly titled The Roofbreaker. It was a crime drama by genre. As you know, this genre is still very popular among viewers.

Very soon, the company’s founders realized that in order to create high-quality films, they needed a special place to make sets, store costumes and props, and, of course, coordinate special effects. It was about a spacious, but not expensive room. That’s right, the partners came and settled in Brooklyn, more specifically in Midwood.

Later, the architect William Stoddard was hired, who, although he was known for his designs of luxury hotels, designed a glass studio for filming underwater and marine scenes. In addition, Stoddart designed a tall chimney on the company’s property that still stands to this day. The Vitagraph officially opened in November 1906, and by 1907, i.e., in just one year, it had become the most profitable film company in America.

Hundreds of silent films and newsreels were made. Borough residents were involved in filming, or ordinary passersby were asked to be extras. It is also known that the company did not shy away from renting houses and even furniture from neighbors to bring life stories to life in films.

What went wrong?

Until 1916, The Vitagraph studio occupied a small acre of land in Brooklyn. It became famous for its comedies, which featured John Bunny, the most popular silent film comedian in the United States before the advent of Charlie Chaplin. The studio’s joint-stock company had more than 100 shareholders.

Unfortunately, however, J. Stuart Blackton and his partners lacked foresight and failed to connect their studio with a movie theater chain. In contrast, their competitors realized at the same time that they needed to show their films somewhere.

The Famous Players-Lasky company, owned by Adolph Zukor and Jesse Lasky, used the Paramount movie theater chain. Marcus Loews of Loews Inc., on the other hand, bought the Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer studios precisely to provide films for his theaters. As a result, in the early 1920s, The Vitagraph could not find screens to show its films. Unfortunately, the era of film production in Brooklyn did not last long.

Sources: